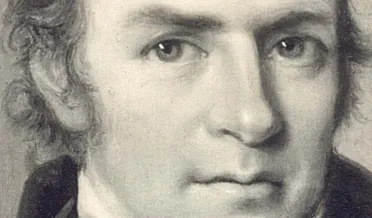

Thomas Telford, the canal builder

Thomas Telford (1757-1834) went from a poor shepherd to one of the world's foremost engineers. He made an eventful journey through life and is still today a role model for many in the engineering industry. During the work they did together, Baltzar von Platen and Thomas Telford became very good friends and exchanged letters frequently right up until von Platen's death in 1829.

An invaluable effort for the Göta canal

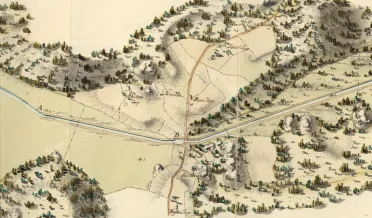

On August 8, 1808, Thomas Telford came to Sweden together with two assistants to assist with their knowledge regarding canal construction. Five years earlier he had begun the construction of the Caledonian Canal in Scotland and he was a highly sought-after engineer with many irons in the fire. Baltzar von Platen needed his advice and help with measuring, weighing, determining the positions of the locks and laying out the canal itself, a job they completed together in only 20 days. In the following weeks, they then worked together on the basis for the Riksdag's decision on a possible canal construction. The report was attached to the colored folders with maps and other things that were given to King Karl XIII. With the report as a basis, the king then issued the letter of privilege on April 11, 1810, which gave Baltzar von Platen permission to start building the Göta canal.

In 1813, Telford came back to Sweden and inspected how the canal construction progressed. He then brought with him blueprints for locks and bridges, and had also managed to get the English government's approval to share the latest technology in the form of newly developed tools. Later that year, Thomas Telford sent over a number of lock builders to train the Swedish workers on the canal construction. Von Platen in turn sent over two young gentlemen, Johan Edström and Gustaf Lagerheim, to learn in England with Telford. There they spent over 9 months before returning home, full of new impressions and knowledge. These came in handy when they then became responsible for each part of the canal construction.

Thomas Telford and Baltzar von Platen were two men of the same spirit. They were both very thorough in everything they undertook, and took pride in always completing their projects. Strong-willed, straightforward and honest as they were, they got along very well and their friendship stayed strong over the years. Baltzar von Platen traveled over to England in 1822 and spent 5 weeks traveling around with his friend. In a later letter to him, von Platen writes that he will always remember this time and says that he has Telford to thank for all the success he has had in recent years. The exchange of letters continued diligently right up until von Platen's death in 1829.

Laughing Tom - The Shepherd's Son

Who then was this man who came to mean so much to Baltzar von Platen, the Göta canal and Sweden? It all began in a small village in Scotland, near the border with England, where Thomas Telford was born on August 9, 1757 as the only son of John and Janet Telford. The father was a shepherd and the family lived in a very simple and spartan cottage in Eskadale in Dumfries, not far from the town of Langholm. When Thomas was only a few months old, the father died and Janet became a widow with sole responsibility for her son. They had to move to, if possible, an even worse cabin that they shared with another family. Friendly neighbors helped with the necessities of life, and the widow did some work for the farmers while their wives looked after the son. When Thomas himself was of age, he began to guard sheep in the summer and look after cows in the winter. At the same time, he attended the parish school where he learned to read, write and count. The parish school was attended by children from all social classes, which contributed to Thomas developing his social skills.

Although Thomas Telford's upbringing was marked by poverty and hard work, he was a happy and humorous person who became known as "Laughin Tam", laughing Tam. Thanks to his easygoing nature, he got along well with most people, and some of his closest friends came from finer families, which later benefited him in his career. He was a kind soul who cared about his fellow men and throughout his life he kept in touch with his childhood friends.

The Apprentice

When the time came for Telford to decide on a career, there wasn't much to choose from. In the end, however, he got hooked on stonemasonry and was sent as an apprentice to a stonemason, but he only lasted a few months there. His master treated him so badly that he ran away to his mother. His cousin Thomas Jackson then came to the rescue and arranged for him to continue his apprenticeship with a quieter master in the town of Langholm. The town was small and everybody knew everybody, and after only a short time a Miss Pasley heard of the laughing stonemason's apprentice and invited him home to tea. She came from a fine, old family and lived in one of the better houses in town. She let Thomas borrow books from her private library, which laid the foundation for his love of literature but also contributed to his growing thirst for knowledge. Throughout his life he almost always had a book in his pocket from which he read a few lines as soon as the opportunity arose.

During the time in Langholm, he worked hard and gained thorough experience of a stonemason's everyday life. Eventually he became really good with a hammer and chisel, and one of the first things he did as an adult was to erect a tombstone for his father with a beautiful inscription. When the apprenticeship was over, he immediately began working as a stonemason. He was involved in many house constructions and helped build a bridge over the River Esk that runs through Langholm. He was very proud of his contribution and to this day you can see stones in the bridge bearing his mark.

Edinburgh, an old city with new possibilities

After a few years, Telford felt that his home district could no longer afford him further opportunities for advancement in his profession, and he decided to try his luck in Edinburgh. He took his pick and pack and set off on foot for Scotland's old capital, arriving just in time. The rich began to leave the old, run-down parts of the city, Old Town, and had new houses built in what naturally came to be called New Town. Skilled masons and other workers thus did not have to go without work.

With great zeal Telford threw himself into his new existence, and thorough as he was, he spent many moments making detailed drawings of the old buildings of Edinburgh in order to learn more about architecture. His thoroughness and willingness to understand everything from the ground up meant that he was constantly developing and broadening his views, both personally and professionally.

London looms

In 1782, after two years in Edinburgh, Telford returned to his home village and visited all his childhood friends, former workmates and of course his dear mother. Soon, however, it was off again, and this time on horseback to London. With a letter of introduction from Miss Pasley's brother, a merchant in London, he sought out Sir William Chambers, who was the architect for the expansion of Somerset House. He was immediately hired and quickly worked his way up to a higher position. In letters home, he expressed his thoughts about starting his own business, together with a very capable colleague, but these plans were crushed by their failure to raise sufficient funds to start a company.

In 1784, Telford instead became an overseer on the construction of a house designed by Samuel Wyatt, while overseeing the building work of a church. He also managed the work at Portsmouth's docks, where he had the opportunity to familiarize himself with the construction of wharf and dock buildings. His reputation spread quickly and he was constantly offered new opportunities to advance. He became an inspector and supervised the repair work of roads, bridges and buildings of various kinds. With that, his career took off and he got more and bigger assignments.

In 1793, to his own surprise, he was asked if he wanted employment as an engineer on the Ellesmere canal (now the Llangollen canal) which was to be built in Wales. He accepted the assignment and thereafter always came into question when it came to canal construction. He built an impressive aqueduct according to his and his colleague William Jessop's drawings, the very famous Pontcysylltea aqueduct. Many are the bridges and aqueducts that came from his designs, and although he was not the first to use iron as a building material, he was the one who recognized its advantages and developed its utility.

An incredibly productive man

Back in Scotland, Telford became responsible for expanding the almost non-existent road network in the Scottish Highlands. As usual, he took up his new duties with great enthusiasm and thoroughness. In order to prevent further emigration from the poor and desolate regions, it had been concluded that more and better roads were required for the outlying communities to grow and prosper. The people there were poor and far behind in the development of education, agriculture and trade. Some sections of the almost non-existent road sections were so difficult to drive that the travelers were forced to travel on foot. Carriages were scarcely available and all the bandit gangs that ravaged the areas meant that many of those who needed to travel there, wrote their wills before they left. In other words, the need for safe, passable roads was great!

When the road construction was in full swing, attention turned to the coastal cities. Protective harbors were of great importance to fishing and Telford rebuilt many of these on behalf of the Norwegian Fisheries Agency. It was a big job as many of the ports were so-called natural ports and very little had been done to them. The winds blew almost straight in and did not provide much protection for the ships trying to escape the waves of the sea when it stormed.

Almost everywhere you turn in England, Scotland or Wales, you find traces of this outstanding man. The Göta Canal's sister canal, the Caledonian Canal, which was built in almost the same period, is another example and the Menai Bridge in North Wales is another. Thomas Telford is responsible for almost 1,600 km of road, around 1,200 bridges and countless houses, churches, harbors and piers.

The base in London

Thomas Telford never married. He traveled a great deal for his work and he needed a base as a starting point. Therefore, he rented an apartment in the Salopian coffeehouse, a kind of apartment hotel, in London, and lived there for over 21 years before getting his own house. In addition, he had access to several apartments that could be used by his visitors for lodging and meetings. Salopian became a center for engineers from all over the world and when Telford informed the landlord of his impending move he was very upset.

“But Sir, why? I just paid £750 for you!”

Upon further explanation, it emerged that the incoming landlord paid that sum to the former landlord and he had in turn paid £450 when he took over the running of the business. The increased price showed that Telford had risen in importance to the hotel and Telford's refusal to stay left the current landlord in despair.

Active until the end

As can be understood from his life's work, Thomas Telford was a man who found it difficult to settle down idle. He wrote reports on various investigations well into his old age, and his advice and opinions were much sought after. Until his death, he was the chairman of The Institute of civil Engineers and he cherished the gatherings of engineers and the exchange of ideas within the institute. When he died on 2 September 1834, aged 77, he left a large bequest to the institute.

His old hometown also received grants that would be used to buy new books for the library, which had previously received donations in the form of books. It was very important to him that everyone had access to the knowledge that was to be found in the literature. Thomas Telford was buried in Westminster Abby in London, where a plaque still shows where he lies today. There is probably no one more worthy of this honor than the young shepherd, who came from such small circumstances and became so important to the development of England, Scotland, and Wales. A long and productive life was over, but his spirit lives on through the many engineers who follow in his footsteps.